I read short fiction seldom, which makes me an odd choice to review an anthology of it. Let me get that caveat out there before everything else: although I know what I like, my ignorance of the form is vast.

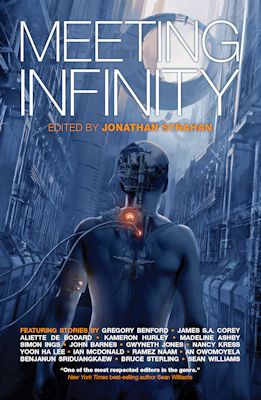

Meeting Infinity is the fourth in a series of science fiction anthologies out of Solaris, curated by award-winning editor Jonathan Strahan. It comprises sixteen pieces of short fiction by James S.A. Corey, Benjanun Sriduangkaew, Simon Ings, Kameron Hurley, Nancy Kress, Gwyneth Jones, Yoon Ha Lee, Bruce Sterling, Gregory Benford, Madeline Ashby, Sean Williams, Aliette de Bodard, Ramez Naam, John Barnes, An Owomoyela, and Ian McDonald, as well as an introduction by the editor.

Strahan suggests in his introduction that the theme of the anthology is the impact of profound change on human beings:

“I asked a group of science fiction writers to think about the ways in which profound change might impact on us in the future, how humanity might have to change physically and psychologically, to meet the changes that might be thrown at us in the next fifty, the next hundred, the next five hundred years and beyond.”

Profound change should have a profound impact. I wish, then, that I could say that more than a handful of the stories in this anthology stuck with me once I closed the covers on this volume. But out of sixteen stories, only five left any real impression—and in two of those cases, the impression was decidedly unfavourable.

Simon Ings’ “Drones” is about a near-future Britain where all the bees have died and pollination has to be carried out by hand. Alongside the loss of bees, a combination of sickness and social factors have led to men substantially outnumbering women. Dowries for women and arranged marriages between wealthy men and a handful of women appear commonplace. The main character of “Drones” is a bland bloke who spends the length of the story musing about women and remembering his brief brush with marriage, and longing for a family of his own, until his dying brother passes on to him his own wife and children at the conclusion.

Oh, and spitting at other people, and consuming piss, appear to have some kind of ritual significance. If there was a point in here anywhere beyond patriarchal existential angst and (wish-fulfilment?) fantasy, I missed it.

Sean Williams “All The Wrong Places” is a story of a stalker. It’s probably not supposed to read as the story of a stalker, but it really does. (A lot like Greg Brown’s “Rexroth’s Daughter,” that way.) After a relationship lasting a little over a year, the narrator’s girlfriend leaves them. And they follow. Multiple iterations of themself, following her to the furthest reaches of human space and time, until they’re the last individual human left and they can’t even remember their own name.

That’s the straightforward reading. The reading made possible by the last pages is that the narrator is the girlfriend, forever trying to catch up to herself. Which turns a stalker story into something that, while less conventional, is a Moebius strip without an emotional core. Where’s the bloody point?

I like stories to have some kind of emotional catharsis or thematic point.

Apart from these two, the majority of the stories in Meeting Infinity are diverting but not memorable. At least, not to me. (I might be a difficult reader to satisfy.) But three—Benjanun Sriduangkaew’s “Desert Lexicon,” Aliette de Bodard’s “In Blue Lily’s Wake,” and An Owomoyela’s “Outsider”—left a real mark. In very different ways, they’re about choices and consequences—making them, living with them, the sheer dialectical ambiguity of being human—in ways the other stories in the anthology are simply not. “In Blue Lily’s Wake,” for example, a young woman and an old woman come to terms with their responsibility for decisions that caused a significant amount of suffering, eleven years after a terrible plague. In “Desert Lexicon,” a terrible journey across a desert filled with war machines becomes a character-study in choice and moral ambiguity. And in “Outsider,” a society that has engineered itself—and its members—to remove conflict by reducing autonomy finds itself threatened by the arrival of a refugee from Earth.

The thematic and emotional weight of all three stories lies in the unanswerable ambiguity of their moral arguments: what is it to be human? What, being human, are the consequences of a person’s choices? What do we take responsibility for, and what responsibilities do we refuse? It doesn’t hurt that all three authors have a very deft facility with their prose.

As an anthology, I’m not particularly impressed with Meeting Infinity. But the best of its stories really are very good.

Meeting Infinity is available now from Solaris.

Liz Bourke is a cranky person who reads books and other things. She has recently completed a doctoral dissertation in Classics at Trinity College, Dublin. Find her at her blog. Or her Twitter.